As a health and fitness specialist with over 15 years of clinical experience, I've witnessed firsthand how body mass index correlates with long-term health outcomes. This comprehensive guide examines the scientific connections between BMI and chronic disease risk, offering evidence-based prevention strategies that can help you maintain optimal health. The information presented is supported by current research and guidance from leading health organizations including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and National Institutes of Health (NIH).

What BMI Reveals About Your Health: Understanding the Basics

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a screening tool that uses a mathematical formula based on height and weight to categorize individuals into weight status groups. The formula—weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m²)—provides a numerical value that healthcare providers use to assess potential health risks. According to the CDC, BMI is "a reliable indicator of body fatness for most people" and is "an inexpensive and easy-to-perform method of screening for weight categories that may lead to health problems".

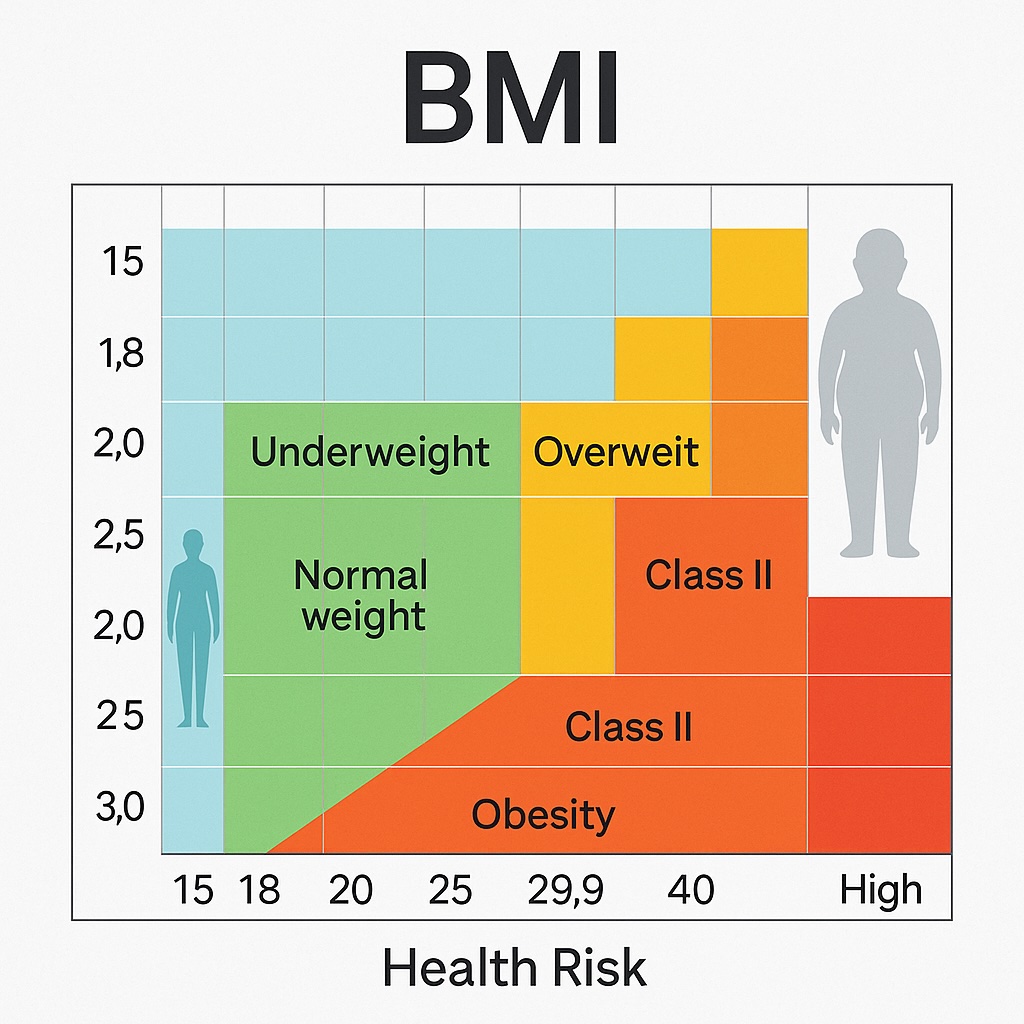

Standard BMI classifications for adults as defined by the CDC and WHO include:

- Underweight: Below 18.5

- Normal weight: 18.5–24.9

- Overweight: 25.0–29.9

- Obesity Class I: 30.0–34.9

- Obesity Class II: 35.0–39.9

- Obesity Class III (severe obesity): 40.0 and above

While BMI offers valuable insights, it's important to recognize its limitations. This measurement doesn't distinguish between muscle and fat mass, nor does it account for where body fat is distributed. The CDC acknowledges that "BMI is a screening measure and should be considered with other factors when assessing an individual's health". Despite these limitations, large-scale population studies consistently demonstrate that BMI remains a reliable predictor of chronic disease risk when used appropriately.

You can easily calculate your own BMI using online tools like the BMI calculator at https://calculators.im/bmi-calculator, which provides instant results and health risk assessments based on your measurements.

The Scientific Link Between BMI and Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death globally, and elevated BMI significantly increases this risk. According to the American Heart Association, "The global obesity epidemic is well established, with increases in obesity prevalence for most countries since the 1980s. Obesity contributes directly to incident cardiovascular risk factors, including dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and sleep disorders".

The Framingham Heart Study, one of the longest-running epidemiological studies, established that each unit increase in BMI is associated with a 5% higher risk of heart failure in men and 7% in women, even after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors.

How exactly does excess weight impact your cardiovascular system? Research has identified several pathways:

- Hemodynamic Changes: Higher body weight increases blood volume and cardiac output, leading to increased workload on the heart.

- Metabolic Alterations: Excess adipose tissue, especially around the abdomen, contributes to insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia.

- Inflammatory Processes: Fat cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction.

- Structural Adaptations: Over time, the heart undergoes structural changes, including left ventricular hypertrophy, which can impair cardiac function.

The relationship between BMI and cardiovascular risk follows a J-shaped curve, with both very low and elevated BMI associated with increased mortality. However, the risk rises more steeply with higher BMI values, particularly for conditions like coronary heart disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.

Research shows that individuals with a BMI above 30 kg/m² have double the risk of developing heart failure compared to those at normal weight. Even more concerning, the probability of heart failure increases dramatically with the duration of obesity—studies indicate a 66% probability after 20 years of obesity and a staggering 93% after 25 years.

How Elevated BMI Increases Type 2 Diabetes Risk

The relationship between BMI and type 2 diabetes is perhaps one of the most well-established in medical literature. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), "Overweight and obesity increase the risk for many health problems, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, joint problems, liver disease, gallstones, some types of cancer, and sleep and breathing problems".

A BMI above 30 kg/m² increases diabetes risk by approximately 10-fold compared to individuals with a BMI under 23 kg/m². The CDC reports that approximately 23% of U.S. adults with obesity have diabetes.

Several mechanisms explain this strong association:

- Insulin Resistance: Excess adiposity, particularly visceral fat, impairs the body's response to insulin, which is the primary metabolic abnormality in type 2 diabetes.

- Beta-Cell Dysfunction: Chronic exposure to elevated glucose and fatty acids leads to dysfunction of pancreatic beta cells, reducing insulin production over time.

- Chronic Inflammation: Obesity promotes a state of low-grade, systemic inflammation that contributes to insulin resistance and pancreatic beta-cell damage.

- Adipokine Imbalance: Fat tissue produces hormones and signaling molecules that, when imbalanced, can disrupt glucose metabolism.

It's worth noting that diabetes risk varies by ethnicity at the same BMI level. Research has shown that South Asian, Black, and Chinese individuals develop diabetes at lower BMI thresholds (24-26 kg/m²) compared to White populations (around 30 kg/m²). This highlights the importance of considering ethnicity when assessing diabetes risk based on BMI.

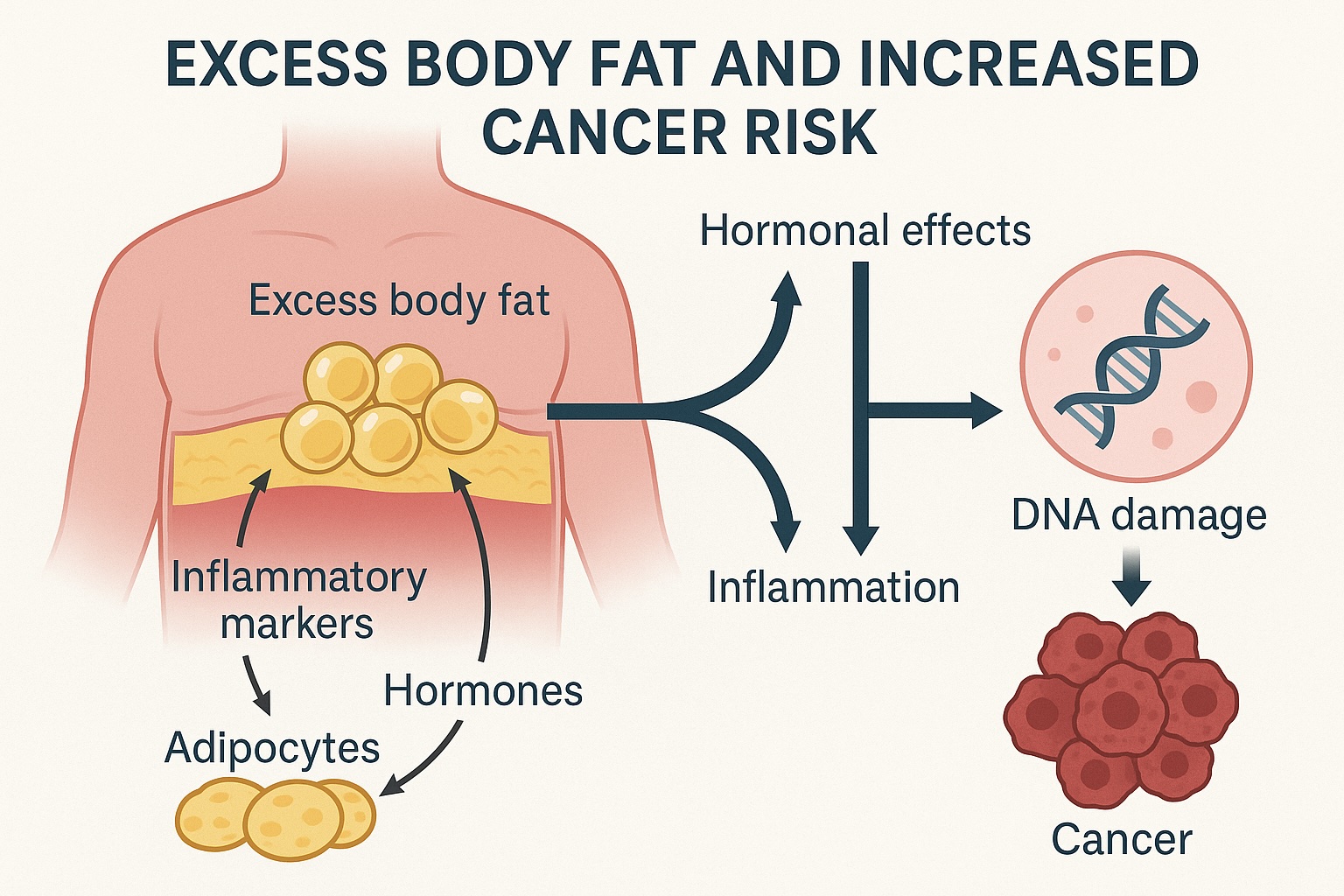

BMI and Cancer: The Hidden Connection

The relationship between BMI and cancer is complex but undeniable. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), "Compared with people of healthy weight, those with overweight or obesity are at greater risk for many diseases, including diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and at least 13 types of cancer".

The NCI further reports that excess weight is linked to increased risk of at least 13 different types of cancer, which together represent about 40% of all cancer diagnoses in the United States.

The strongest associations are observed for:

- Endometrial cancer (risk increases 2-4 times)

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma (risk increases 2-3 times)

- Liver cancer (risk increases 1.5-4 times)

- Kidney cancer (risk increases 1.5-2.5 times)

- Pancreatic cancer (risk increases 1.5-2 times)

- Colorectal cancer (risk increases 1.2-1.5 times)

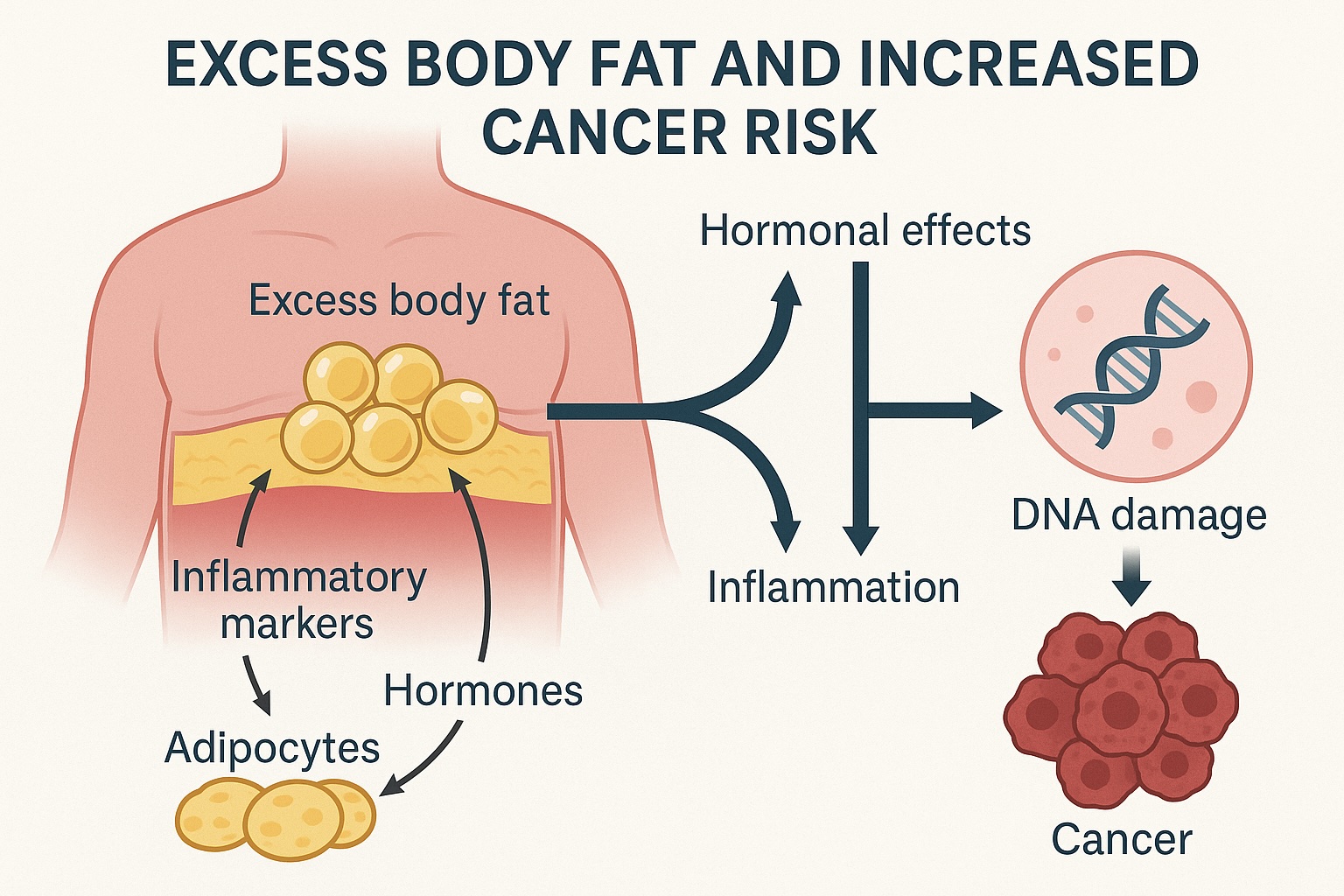

Several biological mechanisms explain these connections:

- Hormonal Effects: Excess adipose tissue increases production of estrogen, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which can promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis (programmed cell death).

- Chronic Inflammation: Obesity-related inflammation creates an environment that favors tumor development and progression.

- Altered Metabolism: Changes in metabolism associated with obesity can create conditions that favor cancer cell growth.

- Oxidative Stress: Obesity increases oxidative stress, which can damage DNA and lead to mutations that initiate cancer.

What's particularly concerning is that having a higher BMI at the time of cancer diagnosis is associated with poorer outcomes, including increased risk of recurrence and reduced survival rates. According to the NCI, "People who have a higher BMI at the time of cancer diagnosis have higher risks of developing a second primary cancer (a cancer not related to the first cancer) in the future". Studies show that individuals with the highest levels of obesity were 50% more likely to die from multiple myeloma than those at healthy weight.

Beyond BMI: Waist Circumference and Other Important Measurements

While BMI provides valuable screening information, research increasingly shows that where you carry your weight may be even more important than the total amount. The National Institute of Health (NIH) acknowledges that "central or abdominal obesity—excess fat around the midsection—poses a greater health risk than fat distributed in other areas of the body".

Waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) have emerged as crucial measurements that complement BMI in assessing health risks. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) clinical guidelines, health risks increase significantly when waist circumference exceeds:

- 40 inches (102 cm) for men

- 35 inches (88 cm) for women

Why is abdominal fat particularly dangerous? The National Cancer Institute explains that "visceral fat—fat that surrounds internal organs—seems to be more dangerous, in terms of disease risks, than overall fat or subcutaneous fat (the layer just under the skin)". This visceral fat is metabolically active, releasing fatty acids, inflammatory agents, and hormones that can lead to higher risks of:

- Insulin resistance

- Type 2 diabetes

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia

- Cardiovascular disease

The American Heart Association notes that "at each level of BMI, higher measures of central adiposity, including waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), were associated with a greater risk of coronary artery disease and cardiovascular mortality, including among those with normal weight as assessed by BMI". This phenomenon, sometimes called "normal weight obesity" or "skinny fat," reinforces the importance of looking beyond BMI alone.

For comprehensive health assessment, the CDC recommends considering multiple factors:

- BMI

- Waist circumference

- Medical history

- Health behaviors

- Physical exam findings

- Laboratory findings

Together, these measurements provide a more complete picture of your health status and disease risk than any single metric alone. Many healthcare providers now use combined assessment tools that incorporate both BMI and waist circumference measurements for a more accurate evaluation of health risks.

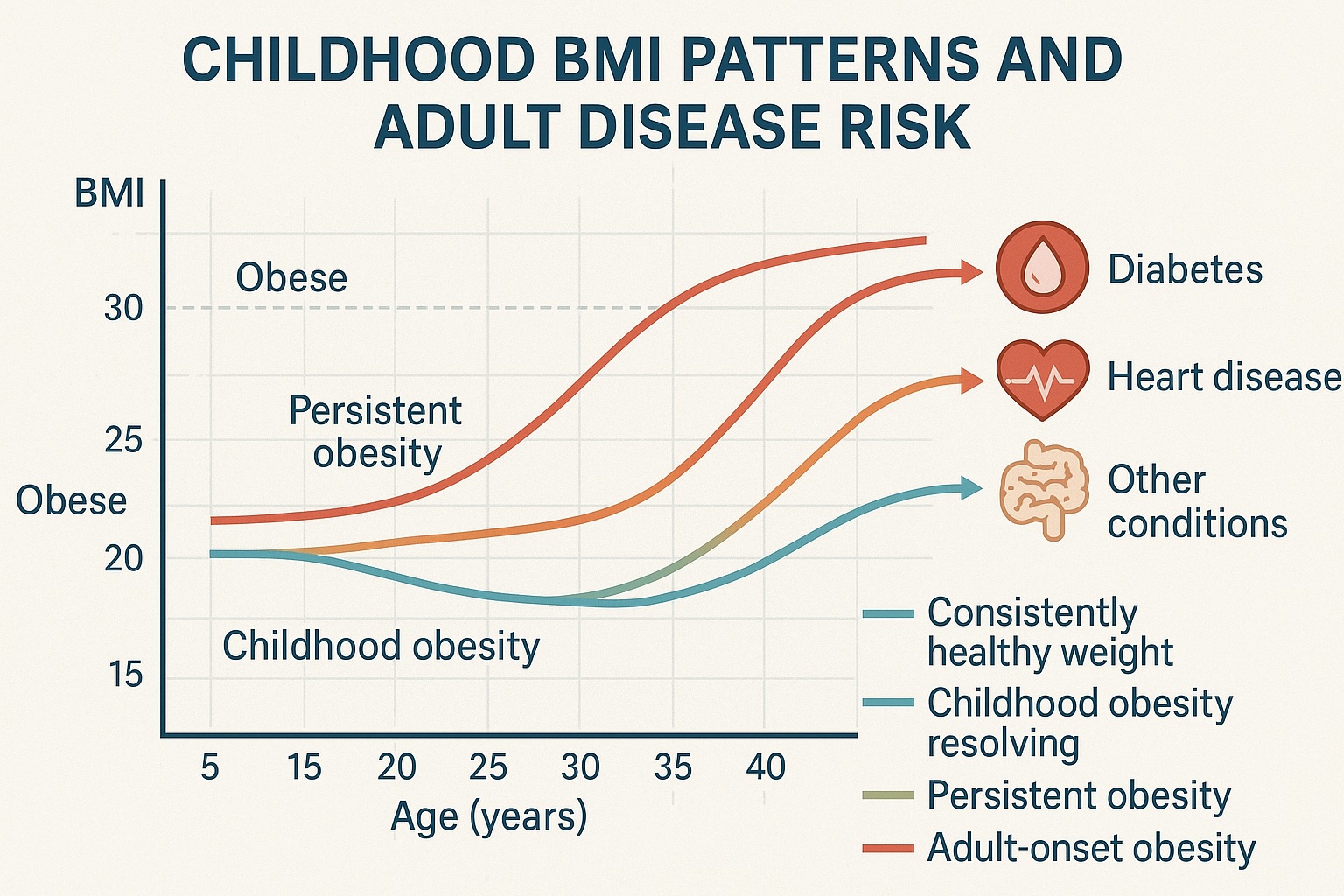

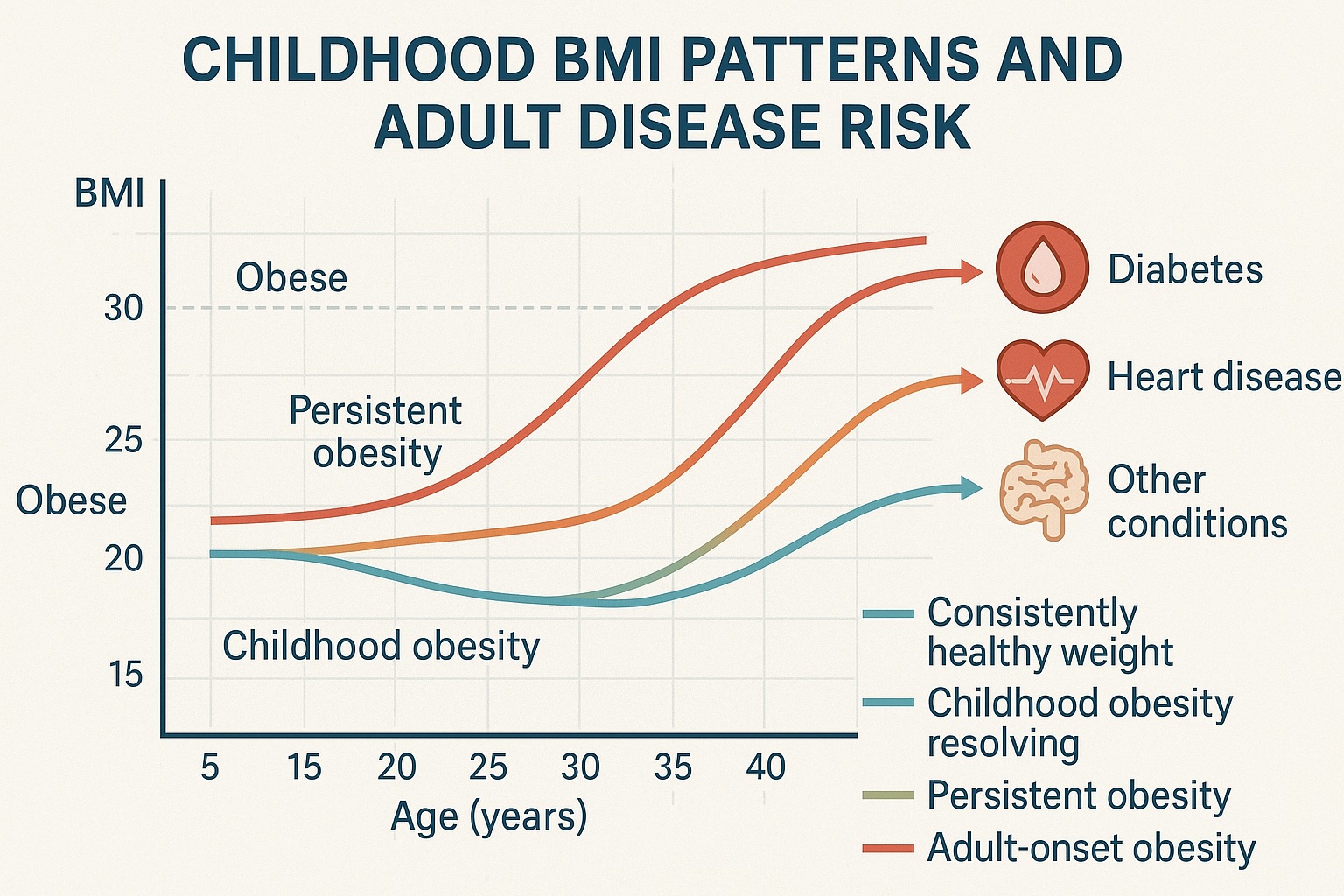

Childhood BMI as a Predictor of Adult Chronic Disease

One of the most compelling areas of research involves the connection between childhood BMI and adult health outcomes. According to the CDC, "Obesity in children and teens is defined as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for sex and age". Longitudinal studies tracking individuals from childhood through adulthood have revealed that elevated BMI during youth significantly increases the risk of chronic diseases later in life.

Research shows that children with BMI above the 95th percentile have:

- 5 times higher risk of adult obesity

- 2-3 times higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes as adults

- Significantly elevated risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality

The NIDDK reports that "Among children and adolescents ages 2 to 19, about 1 in 6 (16.1%) are overweight, more than 1 in 6 (19.3%) have obesity, and about 1 in 18 (6.1%) have severe obesity". These statistics highlight the scale of the issue.

Even more concerning is the relationship between childhood BMI trajectories and health outcomes. Children who maintain elevated BMI throughout development, and particularly those who experience rapid increases in BMI during critical developmental periods, face the highest risk of adverse health outcomes.

The physiological mechanisms explaining these observations include:

- Adipocyte Hyperplasia: Childhood is a critical period for fat cell development. Excess weight during this time can increase the number of fat cells, which persists into adulthood.

- Metabolic Programming: Early life exposures, including nutrition and weight status, can "program" metabolic pathways that influence disease risk later in life.

- Cumulative Exposure: The duration of obesity exposure matters. Early onset means longer cumulative exposure to metabolic abnormalities and inflammation.

- Early Vascular Changes: Obesity in childhood can trigger early vascular changes that accelerate atherosclerosis over decades.

The WHO emphasizes that "childhood and adolescent obesity have adverse psychosocial consequences; it affects school performance and quality of life, compounded by stigma, discrimination and bullying". This evidence underscores the critical importance of preventing and addressing elevated BMI in childhood—not only for immediate health but as a long-term investment in adult health.

Evidence-Based Prevention Strategies for Weight Management

Preventing and managing elevated BMI requires a multifaceted approach that addresses nutrition, physical activity, behavior, and sometimes medical intervention. The CDC notes that "CDC's obesity prevention efforts focus on policy and environmental strategies to make healthy eating and active living accessible for everyone". Here are evidence-based strategies for BMI management and chronic disease prevention:

Nutrition Strategies

- Mediterranean Diet: Abundant research supports the Mediterranean dietary pattern, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, and lean proteins, for both weight management and reduction of chronic disease risk. One major clinical trial found that this dietary pattern reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by approximately 30% in high-risk individuals.

- Portion Control: Simple strategies like using smaller plates, pre-portioning snacks, and practicing mindful eating can help manage caloric intake without requiring strict calorie counting.

- Protein-Rich Diet: Higher protein intake (20-30% of total calories) helps preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss and increases satiety, making it easier to maintain a caloric deficit.

- Limiting Ultra-Processed Foods: These foods are typically energy-dense but nutrient-poor, and their consumption is strongly linked to weight gain and metabolic abnormalities.

Physical Activity Guidelines

- Aerobic Exercise: The WHO recommends "at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity weekly". Research shows that regular aerobic exercise can reduce visceral fat even in the absence of weight loss.

- Resistance Training: Incorporate strength training at least twice weekly to preserve and build muscle mass, which improves metabolic health and functional capacity.

- Reducing Sedentary Time: Breaking up prolonged sitting with short movement breaks can improve metabolic parameters independent of dedicated exercise sessions.

- Active Transportation: Walking, cycling, or using public transit often incorporates more physical activity into daily routines than driving.

Behavioral Approaches

- Self-Monitoring: Regular tracking of food intake, physical activity, and weight is consistently associated with successful weight management.

- Sleep Optimization: Adequate sleep (7-9 hours for adults) helps regulate hunger hormones and reduces cravings for energy-dense foods.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can drive comfort eating and fat deposition in the abdominal area. Techniques like mindfulness, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy can help manage stress-related eating.

- Social Support: Engaging family members, friends, or organized groups significantly improves adherence to lifestyle changes.

Medical Interventions

For individuals with BMI in the obesity range, especially those with weight-related complications, medical interventions may be appropriate:

- Anti-Obesity Medications: Several FDA-approved medications can help with weight loss through various mechanisms, including appetite suppression and reduced fat absorption.

- GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Originally developed for diabetes, these medications have shown remarkable effectiveness for weight management, with some patients achieving 15-20% weight loss. The National Cancer Institute reports that "weight loss through medications approved to treat obesity (including the GLP-1 receptor agonists tirzepatide, semaglutide, and liraglutide) has also been found to be associated with reduced risks of some obesity-related cancers".

- Bariatric Surgery: For severe obesity or obesity with complications, surgical approaches like gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy can produce substantial, sustained weight loss and dramatic improvements in metabolic health.

- Comprehensive Programs: Medically supervised weight management programs that integrate nutrition, physical activity, behavior modification, and medical monitoring often achieve better outcomes than self-directed efforts.

Breaking the Cycle: Interventions That Work for Long-Term Health

Achieving and maintaining a healthy BMI requires more than short-term interventions—it demands sustainable lifestyle changes and sometimes a supportive ecosystem. Here are approaches that research shows are effective for long-term BMI management and chronic disease prevention:

Individual-Level Strategies

- Setting Realistic Goals: Modest weight loss (5-10% of initial weight) can significantly improve health parameters. The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group demonstrated that this amount of weight loss can reduce diabetes risk by up to 58% in high-risk individuals.

- Focus on Health, Not Just Weight: Emphasizing improvements in biomarkers, physical function, and quality of life—rather than just numbers on a scale—helps maintain motivation over time.

- Habit Formation: Structuring environment and routines to make healthy choices automatic reduces the reliance on willpower, which tends to fluctuate.

- Regular Self-Assessment: The CDC recommends periodic reassessment of BMI, waist circumference, and health markers to help catch small changes before they become significant problems.

Community and Environmental Approaches

- Built Environment: The American Heart Association notes that communities designed for active transportation, with accessible recreational facilities and grocery stores, make healthy choices easier.

- Workplace Wellness Programs: Comprehensive workplace initiatives that address nutrition, physical activity, and stress management can reach people where they spend much of their time.

- School-Based Interventions: The WHO emphasizes that "programs that promote healthy eating and physical activity in schools help establish lifelong habits during critical developmental periods".

- Healthcare Integration: When primary care includes regular BMI assessment and connects patients with appropriate resources, early intervention becomes more likely.

Policy Considerations

- Food Labeling: The FDA has implemented clear, understandable nutrition information to help consumers make informed choices.

- Economic Incentives: The WHO suggests that "subsidies for fruits and vegetables and taxes on ultra-processed foods can shift consumption patterns at a population level".

- Healthcare Coverage: The Affordable Care Act has provisions for obesity prevention and treatment services to remove financial barriers to care.

- Physical Activity Infrastructure: The CDC supports public investment in parks, recreation facilities, and active transportation infrastructure to make physical activity accessible to all population segments.

According to the World Health Organization, "The food industry can play a significant role in promoting healthy diets by reducing the fat, sugar and salt content of processed foods; ensuring that healthy and nutritious choices are available and affordable to all consumers; restricting marketing of foods high in sugars, salt and fats, especially those foods aimed at children and teenagers". These multi-level approaches are essential for creating environments that support healthy weight maintenance.

Conclusion: A Personalized Approach to BMI and Chronic Disease Prevention

The scientific evidence is clear: BMI serves as an important indicator of chronic disease risk, particularly for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and numerous cancers. However, the optimal approach to using this information must be personalized.

The WHO emphasizes that "BMI should be considered with other factors when assessing an individual's health". The CDC further recommends considering these additional factors in individualizing BMI interpretation and intervention:

- Family history of chronic diseases

- Ethnicity (different BMI thresholds may apply)

- Body fat distribution (particularly central adiposity)

- Presence of metabolic abnormalities

- Physical fitness level

- Age and developmental stage

- Personal preferences and cultural context

Rather than viewing BMI as a standalone diagnosis, consider it one important piece of a comprehensive health assessment. When combined with waist circumference measurements, laboratory values, family history, and lifestyle factors, BMI provides valuable information for developing tailored prevention and intervention strategies.

According to the WHO, effective approaches to preventing obesity and related chronic diseases include "reducing the number of calories consumed from fats and sugars, increasing the portion of daily intake of fruit, vegetables, legumes, whole grains and nuts, and engaging in regular physical activity (60 minutes per day for children and 150 minutes per week for adults)". The American Heart Association notes that lifestyle interventions such as the Diabetes Prevention Program may be as effective as, if not more effective than, medications for managing weight and reducing chronic disease risk.

By addressing these multiple dimensions and focusing on sustainable lifestyle changes rather than quick fixes, you can significantly reduce your chronic disease risk and improve both quantity and quality of life.

Remember that small, consistent steps often lead to the most sustainable results. Whether you're working to prevent weight gain, achieve modest weight loss, or maintain previous results, the scientific evidence supports a measured, multifaceted approach focused on long-term health rather than rapid transformation.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About BMI for Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/adult-calculator/index.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult BMI Categories. https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/adult-calculator/bmi-categories.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Body Mass Index (BMI). https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/about/index.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(21):e984-e1010.

- Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162(16):1867-72.

- Bhaskaran K, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.6 million adults in the UK. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2018;6(12):944-53.

- Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(5):305-13.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Overweight & Obesity Statistics. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes care. 1994;17(9):961-9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adult Obesity Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult-obesity-facts/index.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Khan NA, Wang H, Anand S, Jin Y, Campbell NR, Pilote L, Quan H. Ethnicity and sex affect diabetes incidence and outcomes. Diabetes care. 2011;34(1):96-101.

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Obesity and Cancer Fact Sheet. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Teras LR, Kitahara CM, Birmann BM, et al. Body size and multiple myeloma mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. British Journal of Haematology. 2014;166(5):667-76.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. NIH Publication No. 98-4083. 1998.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risk. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/risk.htm (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2019;7(9):715-25.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity. https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(6):393-403.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Childhood Obesity Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity reviews. 2008;9(5):474-88.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(25):e34.

- Leidy HJ, Clifton PM, Astrup A, et al. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2015;101(6):1320S-9S.

- Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell metabolism. 2019;30(1):67-77.

- Vissers D, Hens W, Taeymans J, Baeyens JP, Poortmans J, Van Gaal L. The effect of exercise on visceral adipose tissue in overweight adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2013;8(2):e56415.

- Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes care. 2012;35(5):976-83.

- Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA. Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(1):92-102.

- Chaput JP, Tremblay A. Adequate sleep to improve the treatment of obesity. CMAJ. 2012;184(18):1975-6.

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, et al. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of "comfort food". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(20):11696-701.

- Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67(1):132.

- Srivastava G, Apovian CM. Current pharmacotherapy for obesity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2018;14(1):12-24.

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(11):989-1002.

- Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. New England journal of medicine. 2007;357(8):741-52.

- Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, Tsai AG. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: a systematic review. Jama. 2014;312(17):1779-91.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(6):393-403.

- King WC, Bond DS. The importance of preoperative and postoperative physical activity counseling in bariatric surgery. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2013;41(1):26-35.

- Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of 'habit-formation' and general practice. British Journal of General Practice. 2012;62(605):664-6.

- Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, et al. Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126(12):1514-63.

- Anderson LM, Quinn TA, Glanz K, et al. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;37(4):340-57.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health: Childhood overweight and obesity. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/ (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- LeBlanc E, O'Connor E, Whitlock EP, Patnode C, Kapka T. Screening for and management of obesity and overweight in adults. Evidence Syntheses. 2011;89.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/changes-nutrition-facts-label (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Affordable Care Act (ACA). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001. 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Active People, Healthy Nation. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/activepeoplehealthynation/index.html (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- Calculators.im. BMI Calculator. https://calculators.im/bmi-calculator (Accessed May 2, 2025)

- WebMD. BMI Calculator for Men & Women: Calculate Your Body Mass Index. https://www.webmd.com/diet/body-bmi-calculator (Accessed May 2, 2025)

This article provides general health information and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers before making changes to your diet, exercise routine, or medical treatment plan.